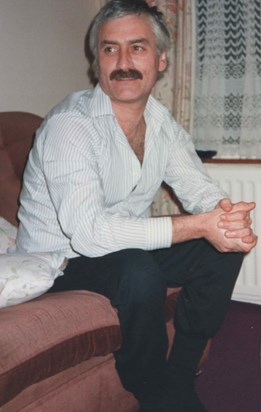

It was with sadness we learned of the death of Ulster Television colleague Colm McWilliams who, as news editor, steered the news room reporters through The Troubles with dedication and compassion. All those who worked with him respected his judgement through difficult times and his care for his staff, be they front of camera, film crews, secretaries or runners. He was a fine journalist with a nose for a story and an understanding of how it could develop. Despite the pressures he had a ready smile and words of support.

We send our sympathies and love to Christine and Colm’s family.

What a wonderful way to embark on a new year when you have been recognised for your service to others. Congratulations to all those who appear on the weekend honours list, especially my friend Pamela Ballantine and James Martin who both can put MBE after their name. It’s a thrill to receive that letter to say the queen or king is minded to recognise your life story but you mustn’t tell anyone until the list is released on the eve of 1st January. Very difficult! Then there’s the build up to ‘the day’, for me it was Buckingham Palace and Prince William as he was then. What an experience awaits the recent recipients and I wish them well on their success.

So here we are New Year’s Eve and a time of looking back and looking forward and both are difficult for many. Last year was one of horror world wide and that doesn’t look like changing anytime soon but we must hope and do what we can to promote positivity. I remember asking Paddy Scott a wonderful gentleman, the best journalist of his time who died a good few years ago at 93; when I asked him what I could do to improve the situation during The Troubles he said, “The Bible says Love your neighbour , care for those on each side of you, then go down the road and across the road and then in the next street and so on until you care for everyone you know and everyone you meet.” I know what he meant but it’s not always possible to turn the other cheek especially when frustration builds in a relationship and tensions get too much people are likely to strike out. This time of year presents such problems in many homes and there are other problems, young men and women out and about, parties and pubs, too much to drink and bad decisions made. May this night of celebration be a safe and happy one.

Talking of Paddy Scott, he was the man who taught me the word camaraderie and who worked as a producer in Ulster Television until his retirement. He died in 1999 aged 93 and a light went out. In the early 60s we lived nearby each other, off the Antrim Road in north Belfast and he often gave me a lift home in his little blue Volkswagen ‘beetle’, his voice high with enthusiasm as he talked of his journalistic life. He then graduated to a Fiat which his friend and director Andy Crockart christened the ‘jet propelled rosary bead’.

In 1923 Paddy became a pupil at St. Malachy’s College and he had a baptism of fire when he first arrived in Belfast from his home in Carrickfergus. Walking from York Street train station to the school on the Antrim Road, Paddy first came across sectarian graffiti on gable walls and experienced the shock of seeing blood on the pavement where someone had been shot dead the previous night. On top of this, his best friend’s father was murdered in his public house. Paddy attributed these experiences and the impact of sectarianism as the impetus to become a journalist.

“I felt that the only way to overcome this problem was through communication and education.”

Before he died the veteran journalist James Kelly told me he well remembers Paddy at Queen’s University when he was editing the RAG magazine. He remembers the students cat-calling to the MP’s going into Parliament which was situated in the Presbyterian Church’s Assembly College from 1921 until 1932. “There was the two faces of opposition, Craigavon and Joe Devlin. The MP’s arrived in the train with top hats and the boys came running out of the students union with big sticks and began tipping their hats off. There was a police baton charge and Paddy was in the middle of it!”

Throughout his working life he was in the middle of the action. He was involved with a number of papers including the Irish News, the Irish Press and the Irish News Agency heading their Belfast bureau. His life was often under threat but the story was paramount and these are some of them, told to me on the many chats we had throughout the years.

On a bitter, wet night in November 1952 he was first on the scene at the infamous Patricia Curran murder scene at Whiteabbey, a peaceful little village between Belfast and Carrickfergus. He talked his way into the house only hours after her body had been found in the wooded driveway of her home, the 19 year old Queen’s university student had been stabbed thirty seven times. Paddy knocked on the back door which was opened by Sir Lancelot Curran, in his time Lord Justice of Appeal, Northern Ireland and Member of Parliament for Carrickfergus. He’d been Attorney General for Northern Ireland and a member of the Privy Council of Northern Ireland. Now he was a distraught father, reeling in shock. In the aftermath of finding his daughter stabbed to death, standing in his kitchen, Paddy convinced him that he’d be better to talk to one journalist about his daughter’s violent death rather than face dozens.

As a result, Paddy left with an exclusive report and a picture which was syndicated around the world. It was only the beginnings of a story which he followed up as it unfolded over the months yet remains unsolved to this day.

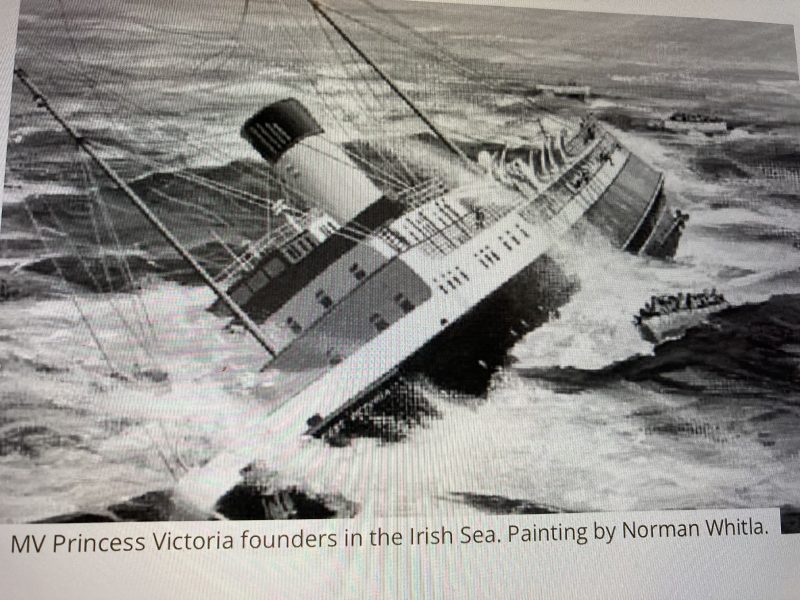

When the British Railways car ferry Princess Victoria sank on Saturday 31st January 1953 in the North Channel off Donaghadee, Co. Down, bodies were being washed up, survivors pulled out of the freezing sea, many taken to the town’s Imperial Hotel, headquarters of the emergency operation which swung into action. No journalists were allowed near the scene. No one was talking as police protected the terrified passengers who were in shock and incoherent. Paddy was on the fringe of the town and determined to get his story. Someone whispered that there was a terrified young cabin boy in a traumatic state, jibbering in his fear. “Let me try to talk to him,” Paddy suggested to the policeman on duty. “He’s probably from the Islands and he’d talking Scottish Gaelic.” This was enough to gain entrance. “Leave me with him for a while till I calm him,” commanded Paddy. They did, not realising he was a reporter. Paddy was right; the boy would only talk in his native tongue and together with the journalist’s Irish Gaelic they got down to business.

Once he’d heard the whole awful story first hand, right from the beginning of the tragedy, the order to abandon ship at 2 p.m. and arriving ashore, Paddy arranged for the young man to get something to eat and to be looked after as he hi-tailed it back to his desk with the story of the death of the Larne-Stranraer ferry in graphic detail. As a professional he was proud to report that his story beat every other journalist to the front page.

Like Paddy Scott, Belfast Telegraph journalist Malcolm Brodie told me how he remembered the day the Princess Victoria went down. “It was a dreadful day, I’d been due to cover the football match between Linfield and the Scottish team Airdrie but because of the weather that morning, the team called off the trip. The first flush of morning news was over and we were waiting for the sports reports to come in so, like any newspaper office in those days, between noon and three o’clock on a Saturday, the newsroom was dead. Then the phone rang. I picked it up and it was a woman on the Antrim Road. She told me her husband was a sea captain and they’d shortwave radio. She said, ‘there’s a drama in the Lough’. She gave me what details she had and it sounded like the Princess Victoria was battling against big seas. She was right. The ship was fighting hurricane winds of Force 12, over 100 miles an hour, tossing in mountainous seas when the huge waves battered the rear doors, sheering off the bolts and flooding the car deck; tonne upon tonne of seawater swamped the ship and some 135 souls lost their lives.

“I immediately went up to her house and sat in a wee cubby hole under the stairs with the radio as she made cups of tea.”

He may well have heard radio officer David Broadfoot who remained at his transmitter throughout the tragedy, sending messages in Morse code in an attempt to give an exact position for rescue vessels, although he must have know it meant he would not survive. For this selfless action, Broadfoot was posthumously awarded the George Cross, highest UK award for bravery which can be made to a civilian. There were many other awards for gallantry shown that day.

For two and a half hours Malcolm filed his report down the telephone line to the Belfast Telegraph; a young John Cole, later to become a respected BBC political editor, took the copy as the story unfolded. At 4.15 that afternoon, a coaster, The Pass of Dromochter, attempted to pick up survivors but send back a message, ‘nothing can survive in these waters and we’re pulling out.’

Portpatrick Coast Radio Station was giving details as they became available and when he heard figures being talked about, Malcolm did a mental tot in his head and realised the extent of the tragedy.

“My problem was trying to get the boys at the Telegraph to believe what I was telling them – that there could be over 100 people drowned.”

In fact, it was more. On Saturday, January 31st 1953, 179 set sail from Stranraer to Larne on the car ferry Princess Victoria. Only 44 men survived the crossing. Four little children, 29 women and 102 men perished.

There were notable names recorded in the list of dead. Major Maynard Sinclair, MP for Cromac, Minister of Finance and Deputy Prime Minister, was also on board. Major Sinclair was relaxing in the smokeroom when the steward on duty warned that the ship would roll a bit as the weather was rough. At that moment a glass fell off a ledge under a porthole and smashed to the floor. There was a lurch to starboard but she righted herself. A second heavier and more violent lurch threw people across the room breaking chairs and tables. Major Sinclair was thrown to the starboard side of the room. The Princess Victoria never regained an upright position. Sir Walter Smiles Ulster Unionist MP for North Down and Captain James Ferguson who went down with his ship, saluting as the sea engulfed him. But the majority were families, businessmen, passengers and crew taking the routine trip of only a few miles, expecting to leave the shelter of Loch Ryan and move into the North Channel and on to the safety of Larne Harbour. It certainly didn’t happen that way and there were many stories told by the survivors after the tragedy. A First Class steward was manning one of the lifeboats, sitting in the bow and holding on to each side of the boat when a huge wave crashed it against the side of the Princess Victoria cutting off three fingers on each hand. Others swam to life rafts only to be carried away in the raging sea. One lifeboat filled with women and children was swept against the side of the sinking vessel and swamped.

The inquiry into the disaster found the fault lay principally with the ship’s owner and manager, the British Transport Commission, basically because the ship’s stern doors were insufficiently strong for conditions in the North Channel. There was also a failure to provide adequate ‘freeing’ arrangements for seas that may enter the car decks from any source.

Some positive actions were taken as a result of the disaster. Because the standard cork lifejackets were thought to have choked some passengers to death, today lifejackets must be tied tightly and held down if jumping into the sea to prevent them pushing up and causing neck injuries or suffocation. The design of similar ships was examined in the light of the experience and subsequently stern doors were strengthened and the size of scuppers increased.

Like Paddy Scott, later that afternoon, Malcolm Brodie headed to Donaghadee to follow up on his story, but the tragedy he said was when he came back to the Telegraph that evening to find thousands of people standing in Royal Avenue waiting for news. “You’ve got to remember in the early 50s there was no news broadcasting as we have today, no Internet, no mobile phones, so they came to the source of news and that was a newspaper.

“For the first time in its history,” he said “the Ireland Saturday Night carried a news story on the front page rather than sport and we put out a special edition of the paper on the Sunday. It was tragic.” Malcolm was obviously reliving that last day in January as he added sadly, “I lost a mate that day, a fellow Scot.” He’s silent for a moment. “We were to meet that Saturday night as usual and go dancing. It wasn’t to be.”

Despite the many and varied stories he covered during his lifetime, Paddy Scott liked best to talk of the Titanic. So when the James Cameron film was previewed in 1997, I invited him to come with me to Belfast’s Yorkgate Movie House.

He wrote the following handwritten letter to me, probably that same night when he got home. A moving piece of history.

Dear Anne,

The apt expression of the reaction that comes to my mind on seeing and hearing Cameron’s Hollywood version of the Titanic story is contained in a quotation from Macbeth (Shakespeare) – it was a tale told full of sound and fury signifying nothing.

That may seem a harsh appreciation of the three hour version of the Titanic story of which I had a fascination since as a boy of five years and the seventh son (of eight boys) of the chief officer of the Coastguards at the station in Cloughey, on the rocky Co. Down coast between Donaghadee and St. John’s Point at the entrance of Strangford Lough. I saw the Titanic with black smoke belching out of three of her four funnels as she gained speed on dropping her tugs, on her passage to Southampton to begin her maiden voyage to New York and destiny. The Belfast papers reflected all the enthusiasm and pride in this the second of the luxury liners on the slips of the Belfast shipyard. – the Olympic, the Titanic and the Britannic all catering for the emigrant traffic to America from Ireland and Britain and Europe. The three liners were the brain children of three cousins then leading executives of Harland and Wolff ’s shipyard – Lord Pirrie the chairman, Alexander Montgomery Carlisle, managing director and chief naval architect and Thomas Andrews of Comber, a younger member of the linen mill owning family.

Lord Pirrie, engineer and naval architect of H&W where he served his time, was, after Harland himself, the chief architect of the success of the Belfast shipyard. He negotiated the deals with the White Star Line for their transatlantic passenger trade and planned the initial stages of adding to their fleet the three great liners – the Olympic, the Titanic and the Britannic – all at the opening decade of the 1900s.

Of the three ships, the Olympic, the first of the slips was Perrie’s favourite. It was the Olympic which brought his body back for burial in Belfast City Cemetery when he died from a heart attack during a cruise in American waters.

The plans for the three liners were agreed by Pirrie and the White Star Line chiefs. He looked after the Olympic design and left his cousin Alexander Montgomery Carlisle, the chief naval architect to succeed him as general manager to look after the Titanic and the preparation of the building of the Britannic on adjoining slips. So Carlisle was the man who built the Titanic and his cousin the youthful Thomas Andrews saw it completed.

Carlisle was a strong individualist, hard working, a disciplined student and apprentice. He took a cold bath every morning before cycling to the shipyard at 7 a.m. and was never late for work during his five years apprenticeship.

“It was an early April day in 1912 when most of those

from the villages of Cloughey and surrounding farms gathered at the Coastguard station in great excitement expectation to see the great liner – the largest and most luxurious in the world – sail into and past Cloughey Bay on her passage down the Irish Sea to begin her maiden voyage to New York from Southampton, collecting passengers at Cherbourg France and Queenstown Ireland on the way. The aim was to capture the record crossing of the Atlantic from the rival transatlantic passenger company.

Everyone knew of the size, luxury and capabilities of the world’s greatest and most luxurious ship.

My home knew all about the ship especially from my brother John, then a third year apprentice in engineering at Harland and Wolff shipyard, who referred to her as “the big boat 401” apparently the number on the shipyard’s list of ships.

The Belfast papers reflected all the enthusiasm and pride in this the second of the luxury liners on the slips of the Belfast shipyard – the Olympic, the Titanic and the Britannic – all catering for the emigrant traffic to America from Ireland Britain and Europe. The three liners were the brain children of three cousins then leading executive of Harold and Wolff’s Shipyard – Lord Perrie the chairman Alexander Montgomery Carlisle managing director and chief naval architect and Thomas Andrews of Comber a younger member of the linen mill owning family.”

Whilst in London, Carlisle was a close friend and admirer of Wickham Steed, the well-known author, who wrote a special feature in his prominent magazine on the Titanic and planned to travel to a humanist convention in America on the maiden voyage of the liner from Southampton. Carlisle went there to see his friend off and his ship and his cousin Andrews who also planned to make the maiden voyage and complete work to be done on the liner while on the crossing.

“It was customary for the managing director and his wife to make the maiden voyage crossing in the ship. But Andrews’s wife was still suffering from postnatal depression after the birth of their first child, a daughter and her doctor advised her not to make the maiden voyage on the Titanic.

Just before the Titanic pulled away from the docks at Southampton, Bruce Ismay, the chairman of the White Star liner noticed Carlisle standing on the quayside near the gangway. He had come to see off his closest friend Stead.

“Are you not coming with us Carlisle?” he shouted. Carlisle replied, “No, I wasn’t asked.”

Later, when the fate of the Titanic was talked about, he was asked. “Would you have gone if he had said ‘Well come along with us.’” He replied. “I would have been honoured to die with my brave and loyal friend Steed.”

Andrews courageously lost his life in the disaster and was last seen advising passengers to put on lifebelts. His last thoughts were about his wife sick at home in Windsor Avenue in Belfast and his young baby daughter. He was among the 1500 passengers who died that night.”

This was an amazing letter to receive only hours after Paddy and I sat and watched Cameron’s film.

During our conversations, Paddy, with his unique memories, later updated the story of the RMS Titanic which struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic just before midnight on 14th April 1912 and sank the next day with the loss of 1520, men, women and children. This total didn’t include stowaways. “The Belfast Evening Telegraph of April 15th 1912 carried reports which were amazingly informative given the short time between disaster and publication. One report from New York spoke of the clamour for news and of ladies sobbing hysterically, one frantically inquiring for news of her sister who was returning from her honeymoon. Later, high-class women pulled on their fur coats, raided their larders and were chauffeur driven to the docks wishing to give what they could to survivors, including their furs. From the day of the disaster, surviving crew members ceased to receive any pay and even in death there was the discrimination between rich and poor. First class passengers were placed in coffins. Canvas bags for the rest.”

Then, from Paddy Scott, my friend and mentor, came the strangest story of all.

“When I became a journalist, on leaving Queen’s University, I happened to meet and then interview an elderly man who lived alone in a street off the Old Lodge Road near Carlisle Circus and Clifton Street. I think his name was Mulholland. He was a stoker by trade. Sitting in his back room one day in front of the wee fire he told me that he stoked the Titanic on her trials and on her way down the Irish Sea to Southampton. This is his story, Anne. It’s spine tingling.”

There and then Paddy Scott stepped back in time to 1929 recount this interview with Mulholland the stoker, word for word. This is Mulholland’s story.

“In 1912 work was hard to come by in Belfast. I was waiting for a stoker’s job in a tramp steamer that would bring me work continuously for much of the year. I was offered the job on the Titanic but I didn’t like short crossings although I agreed to go as far as Southampton. I preferred the long voyages in tramp steamers that took you half round the world’s ports. At the end of these voyages after visiting ports in two or three continents, you’d have a nice pay packet in your pocket. You didn’t save money on a short transatlantic crossing.

“Anyway I made friends with my mate in Belfast, a fellow stoker on the Titanic. On her trials down the Irish Sea he urged me to complete the voyage to New York with him as we got on well working together on the same furnace. I explained my preferences to him about long voyages and told him I’d keep an open mind.

“But my decision was really made by the behaviour of a cat that came on board the Titanic in Belfast and made a home with the stokers. She had a litter of four kittens on board ship and we kept her, looking after the mother cat and her brood broke the monotony of stoking the furnace. But when we docked at Southampton that cat made up my mind for me. Shortly after we tied up, the cat made a survey of the place. I watched her intently. When I saw her catching each kitten by the back of its head and carry each one down the gangway and on to the quayside, I thought, that cat knows something and has decided that the Titanic was no place for her or her kittens to spend their lives. So I took the advice that cat was giving me in a practical way – I said goodbye to my mate and left the ship at Southampton. I gave thanks to God for my choice.

“A few years later, Paddy, my tramp steamer berthed in the port of Valparaiso in South America. I dropped into a pub at the docks for a leisurely pint with a crew colleague. I happened to cast a glance across the bar and my eyes focused on a figure drinking there, something about him which I thought I recognised, something familiar. It was dim where he was sitting in the corner. I looked several times at this man and a movement of his head revealed features like those of my stoker mate on the Titanic. I thought no more about it, Paddy, as I had long given him up as one of the crew lost in the greatest sea disaster. But I kept looking at him. Finally, curiosity got the better of me and I got up and approached him. As I got closer I almost panicked. It was him. He recognised me too. We greeted each other warmly, even emotionally as I thought he was dead and with the other victims of the disaster at the bottom of the Atlantic with the liner.

“When I recovered from the shock of meeting a stoker mate who had come back from the dead, and a few more drinks, I accompanied him back to his ship where he told me how he got off the doomed liner. In the panic and confusion on board the Titanic, he said he made his way through the milling crowds of passengers by various routes and corridors to the upper deck and edged his way towards the rail where a lifeboat hung precariously on ropes. There were women and children on board. An officer called out:

‘Is there anyone here who can row and manage a boat?’

I shouted back over the noise, ‘I can and sail one too.’

‘Get in’ he commanded, ‘and pull away immediately the lifeboat hits the water.’

I got into the crowded lifeboat, did as he told me and pulled

away when it began to float. The relief to be away from the panic was overpowering. We got clear of the Titanic, away from the danger of being sucked down with her. We kept close to the other lifeboats by shouts and whistles. We were, after many hours, picked up by the Carpathia.

‘I was the last to leave the lifeboat and as I was being lifted off I noticed amongst the debris on the floor of the lifeboat a small decorated chain purse used by a young girl to hold her money at a party. I picked it up, put it in the pocket of my jacket.

‘And Paddy, in his cabin he opened the drawer of a small desk and pulled out the child’s vanity party bag. ‘Look at the contents,’ he said. I counted coins, they were all dated before 1912. ‘Keep it, Mulholland,’ he said, ‘in memory of your lucky escape from the Titanic.’

It was obvious that Paddy Scott was moved by the memories that were unfolding as we talked all those years later.

“I was mesmerised Anne by the story of this man Mulholland who walked off the Titanic, lived to meet his mate and hear the story of his survival”.

What a friend Paddy Scott was to so many and what an example of his journalist prowess.